DH Pedagogy for Institutional Change

This is the text of a talk I gave at the Association for Computers and the Humanities conference (ACH2019) on July 24, 2019. I use two examples of text encoding work I did with undergraduate students to reflect on the possibilities of DH pedagogy to push DH from the periphery to the core of what libraries do. After listening to so many wonderful presentations and reading the conference tweets, many of which had to do with the strengths as well as the uneasiness of dwelling in between disciplines, it still feels a little foolhardy to wish for such a thing. Nevertheless, institutions do change. Here, I present one of presumably many strategies for advocating for the future we wish to see.

Introduction

I am Francesca Giannetti and I work at Rutgers University as their Digital Humanities Librarian. I’ll be speaking to you about two text encoding projects involving correspondence collections that I have worked on with students.

I will be presenting a library perspective on the topics of digital humanities pedagogy and the use of digital methods to push for institutional change.

Editor as Social Agent

In this talk, I will walk you through my motivations and strategies as a digital humanist who also exercises a number of more established librarian roles, such as information literacy instruction. My practice is essentially governed by a set of constraints—I’m a librarian who does not have access to a lot of technical or financial support—and an inclination to do interesting digital work that meets some of the demand among our students for rigorous technological engagements. My work always has at least two audiences—the students and my fellow librarians, who are often more interested in seeing how digital humanities work supports longstanding library practice.

Innovation as a Means of Transformation

I’d like to share some initial thoughts about the ways in which digital editing with the Text Encoding Initiative can be an innovative form of knowledge production. Text encoding as a practice is itself rather old, dating to the mid 1980s. The TEI is not what anyone would consider cutting edge at this point, so as a method it’s probably excluded from what we might call “emerging.” So that leaves, in my view, two main routes for novelty and innovation in this area of practice:

- Models (of texts, documents, and processes)

- Subjects (of editions)

TEI editions capture our attention because they implement unusual or striking ideas about representations, or models, of texts. Humanists who encode texts often place great emphasis on the abstract models that their projects instantiate, whether it has to do with what is or is not considered part of the “work,” the aspects of the source material that have been captured and made machine readable, or the relationships in between items or creators that have been made tractable and manipulable. One twist that I’d like to add, and that is not often brought up in written accounts of digital editions, is that text encoding projects can also implement innovative models of process, namely the manner in which the people on the editorial team get the work done. More on that further on.

The second route for innovation has to do with the subject of the edition itself. By subject, I am referring to the stuff, the work, the documents, sometimes by a known author, sometimes not, that the edition proposes to interpret. In the early days of text encoding, there was some sense that the print canon was being reproduced digitally. However, there was also the Women Writers Project, whose aim was to “reclaim the cultural importance of early [modern] women’s writing and bring it back into our modern field of vision”.1 In the intervening decades, still more editions of works by women have come online. And we are seeing the beginnings of a corpus of digital editions of works by authors of color, including Harlem Renaissance writers edited by Amardeep Singh, Roopika Risam, among others. There has been something of a boom in digital editions of life documents such as letters and diaries. Referring back again to models, among the more interesting implementations of correspondence editions has to do with a maximalist approach in which editors analyze the letters of a social circle, and not just one or two correspondents. As Gabriel Hankins has remarked, digital representations of correspondence allow the editor to “do justice to the larger social fields in which letters were written and […] better represent the social dimension of epistolary thinking.”2

My preoccupation with innovation has to do with the goal of transforming librarian practice and participating in the changes taking place in humanities education. I want revolution—of the bloodless sort—and it’s maybe for that reason that I was drawn to the Bourdieusian concept of autonomy. Briefly, in trying to understand the structure of the literary field in nineteenth-century France, and the agency of individuals within it, Bourdieu ascribes greater autonomy to the pole of cultural production that has the greater symbolic capital, which is to say the rule-breakers, the avant garde, the artists who are the least interested in pleasing readers and most concerned with creating what they view to be great art. The opposite pole is economic capital, where he places most mass market cultural production. These creators are capable of earning more, but they also have less artistic freedom in what they produce. This was a fluid, dynamic system, and one of Bourdieu’s goals in analyzing it was to understand the principles animating it.

The Strengths of Weak Capital (😂)

A late study of his on literary editing also captured my attention. In this essay, he observes almost a merging of the poles of symbolic and economic capital. The biggest publishing houses were accumulating most of the money and most of the literary prizes, whereas the small, newer publishers could access, at best, a weakened symbolic capital in the form of the esteem of a few admirers in the know. He notes:

These small, innovative literary presses, if they weigh very little on the fiction market, provide it nonetheless with its raison d’être, its justification for being, and its spiritual point of honor—and in this way one of its principles of transformation. Poor and powerless, they are in some ways condemned to respect the official norms that everyone professes and proclaims.3

The route by which new voices could enter the field of literary production was primarily through these small, poor literary presses, which Bourdieu seems to suggest were the last meritocratic outpost in the literary field of the 1990s. While the analogy to text encoding is not perfect, scholarly editing not being quite the same as literary publishing, the part about being poor and powerless sounded familiar. While I don’t have any solution to propose to the problems of prestige and capital, I’m happy at least that a strength of occupying this corner of the scholarly editorial field is greater autonomy in the selection of one’s texts. This is even more true of pedagogical text encoding projects. The “virtue” of this position is not only a strength, but it is also a “principal of transformation” as Bourdieu puts it. It’s the way we discover, or rediscover, new and marginalized voices that change our perceptions of a given time period, place, or movement.

While I can’t claim to be virtuous, or even particularly innovative, I will turn now to describe my work on text encoding with students and explain how it fits into this notion of transformation.

TEI Projects

The first of these projects, an edition of personal papers held by a former slave, is an independent research project involving the participation of undergraduate research assistants. The Peter Still papers are primarily composed of correspondence relating to Still’s efforts to free his wife and three children who were still enslaved in Alabama.

While I can’t claim that Peter Still has been ignored by scholarship—there are a handful of articles and books written about him—this manuscript collection is not especially well known outside a handful of specialists. One of my aims in creating this edition has been to make the study of the collection more approachable for students.

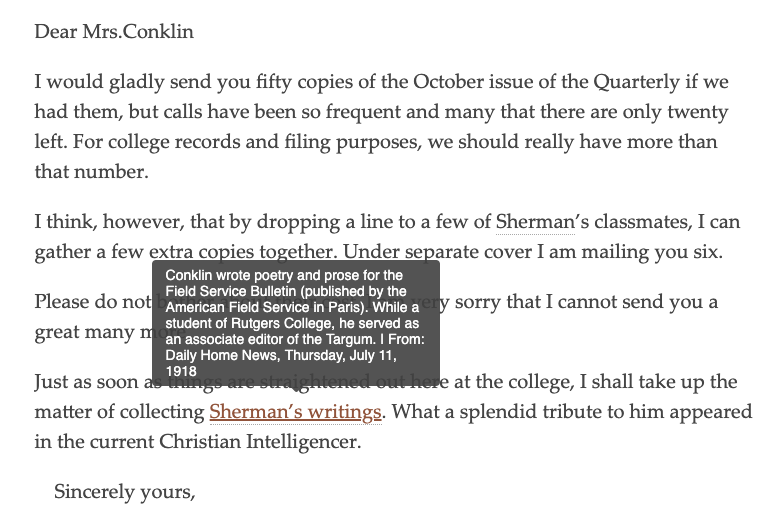

I designed the second project, based upon letters to and from the Rutgers College War Service Bureau (1917-1919), as a two-week unit in a proposed undergraduate course in digital humanities. The collection contains over four thousand letters between the bureau’s director and Rutgers alumni serving in the armed forces during World War I.

With the exception of Joyce Kilmer, a Rutgers College alumnus who had achieved some fame as a poet before he died in the war, none of the letter writers are especially well known. However, the collection does provide avenues for discussion of institutional history, histories of class and race in the military, as well as microhistorical approaches in which personal records and memories are often used as sources. These letters also provide fodder for discussions of what constitutes history and who gets to write it.

Process Modeling

I’ll conclude with a few remarks about process modeling.

A chapter by Julia Flanders and Fotis Jannidis briefly notes that there are different forms of modeling, usually divided into two groups: process modeling and data modeling.4 In their essay, they mostly dwell on the topic of data modeling, but it occurred to me while reading that public service librarianship offers a pretty good process model in that we teach students about the research process. I’ll make a few allusions to The Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education, which is one of our core professional texts. While my fellow librarians, including Harriett Green5 and Mackenzie Brooks6, make arguments for teaching text encoding to develop digital and data literacies, with which I wholeheartedly agree, I sometimes make a simpler argument that text encoding teaches us how to do research.

Evaluating Authority

Placing lesser known figures at the center of one’s research inquiry requires using sources that may appear to be of dubious authority, at least by conventional research standards. Both the Still and the War Service Bureau projects have required basic biographical research to complete the personography entries and analytic annotations. In select cases, the figures in question were well enough known that they could be found in reference books and library databases. Quite a few names were resistant to those techniques. Still received support from some well known abolitionists, but the majority of them were ordinary citizens. One of the undergraduate research assistants I worked with, when she found herself repeatedly falling back on crowdsourced genealogical databases like Find a Grave and Family Search, questioned the appropriateness of these sources for historical research. Given that so much academic literature emphasizes traditional notions of authority, e.g. academic credentials, peer review, these sources understandably seemed dodgy.

We eventually arrived at a more inductive approach to the question of authority: we looked for confirming or contradicting data in our primary sources. When sourcing was provided by these online resources, we evaluated the trustworthiness of those sources. And wherever possible, we cross-referenced our findings with accounts by authors contemporaneous to Still. The information we gathered was inferred and pieced together, with the gaps and silences typical of research on non-canonical subjects. With the limitations and blind alleys we encountered, this approach to our sources drew attention to the situatedness of all information sources, including the authoritative volumes of American National Biography,and the shifting contextual demands of our information need.

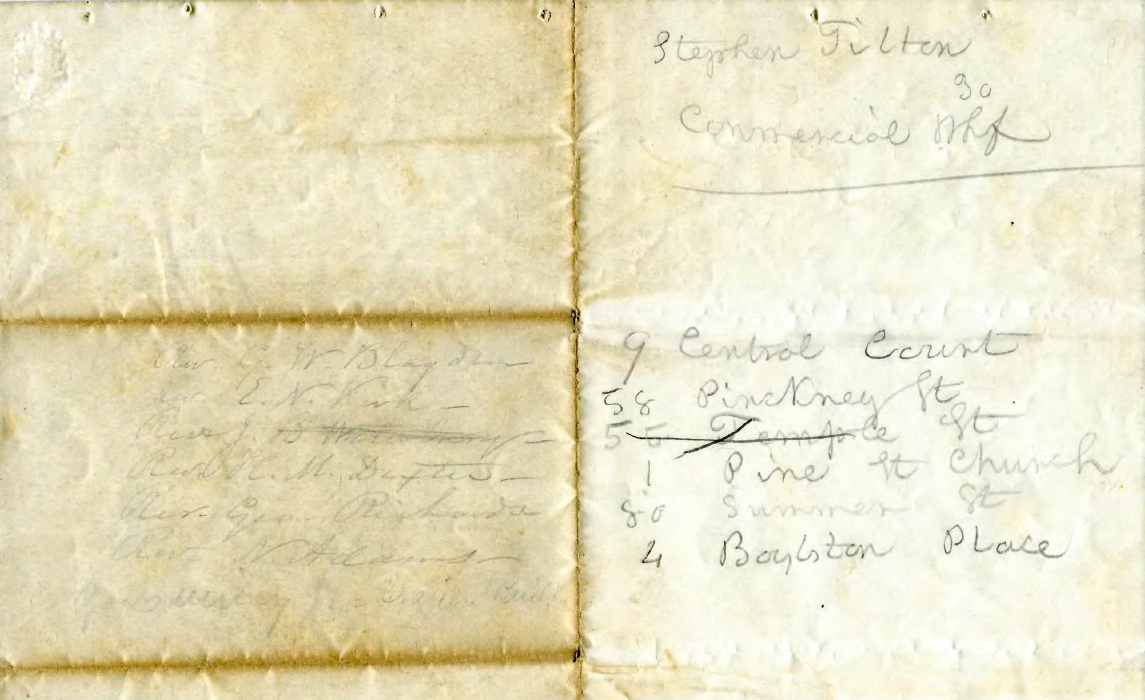

Information Creation as Process

One of the difficult pleasures of text encoding projects is, on the one hand, the need to establish a data model for the project in order to prepare a schema and train encoders, and, on the other, the unavoidable necessity of revising that model as particular features encountered over the course of the work challenge it. An anecdote from the work on the Still papers illustrates how a simple question about encoding a structural feature led to other questions about interpretation, ultimately resulting in the decision to make changes to our model. A question from an undergraduate research assistant about how to encode a pencil-written annotation of Fletcher Webster’s letter of introduction prompted an extended inquiry.

When we initially reviewed her encoding, she asked about representing lists in TEI. Eventually, it struck us that the names of people and the addresses were related and meant to be read across the fold, even if they were written in two different hands. One could imagine, for instance, Still asking Webster for a list of prospects who might be persuaded to help him when presented with Webster’s letter. And indeed, the names of the ministers appear to match Webster’s own hand from the body of the letter. The owner of the second hand is a mystery. While we couldn’t settle this question definitively, it became clear that we wanted to incorporate elements from the TEI manuscript description module for describing changes in hand. In general, the letters of introduction frequently bore one or more postscripts from people other than the principal letter-writer; usually these people wished to convey their support of the letter’s contents. While the initial plan was to capture only the text of these annotations, curiosity about the authors and their motivations—even when the answers to our questions were unknowable—eventually led us to the decision to signal their presence with more robust descriptive markup. In this way, our experience of circling back, reexamining our work, posing new questions, and revising our plan was fundamental to the process of creating the edition, and adhered closely to the Information Creation as a Process and Research as Inquiry frames.

Conclusion

You may be wondering why the first part of my talk dealt with innovation and transformation and the second part addressed this rather well established aspect of public services librarianship having to do with information literacy instruction. The reason for that has to do with my position in a field where we are often in between disciplines and communities. My concern here is with transforming the library community in particular by positioning text encoding and digital editing as a logical bridge between past pedagogical practice and potential present and future roles, one where the data literacies might not be understood as so very specialized and more like the responsibility of many. Since many of us modify our arguments about the value of DH, depending on our (sometimes skeptical) audience, I’d like to conclude by inviting you to comment on your own strategies for persuasion and for transforming disciplinary practices.

Postscript

A longer variation of my remarks may be found in an upcoming issue of The Journal of Academic Librarianship:

Giannetti, Francesca. 2019. “‘So near While Apart’: Correspondence Editions as Critical Library Pedagogy and Digital Humanities Methodology.” The Journal of Academic Librarianship 45 (5): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2019.05.001.

-

Hankins, G. (2015). Correspondence: Theory, Practice, and Horizons. In Literary Studies in the Digital Age. Retrieved from https://dlsanthology.mla.hcommons.org/correspondence-theory-practice-and-horizons/ ↩

-

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1999. “Une révolution conservatrice dans l’édition.” Actes de la Recherche en Sciences Sociales 126 (1): 11. ↩

-

Flanders, J., & Jannidis, F. (2015). Data Modeling. In A New Companion to Digital Humanities (pp. 229–237). Malden, MA; Chichester, West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118680605.ch16 ↩

-

Green, Harriett E. 2013. “TEI and Libraries: New Avenues for Digital Literacy?” Dh+lib (blog). January 22, 2013. https://acrl.ala.org/dh/2013/01/22/tei-and-libraries-new-avenues-for-digital-literacy/. ↩

-

Brooks, Mackenzie. 2017. “Teaching TEI to Undergraduates: A Case Study in a Digital Humanities Curriculum.” College & Undergraduate Libraries 24 (2–4): 467–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/10691316.2017.1326331. ↩

Comments